Nigeria and the Royal Niger Company: The true story

No entity was more instrumental in spreading British interest in the territories – especially the areas surrounding the River Niger, than the Royal Niger Company, which was founded in 1879 as the United African Company.

The course of the River Niger down to the Niger Delta, was first successfully navigated by foreigners in 1829- this being by Richard and John Lander, who travelled the Niger from Kano to the sea in the Niger Delta. From then, a number of attempts were made- financed by the British Government- to establish strong commercial and administrative influence in the surrounding areas. However these efforts were futile and in particular the expeditions of 1832, which was led by British Merchant McGregor Laird and which Richard Lander once more participated and the expedition of 1841, which had Missionary figures and businessmen, were spectacular failures. The former having to be abandoned after they were attacked at Bussa, by hostile indigenes, suffering casualties- Lander in particular died of a Musket-ball injury as a consequence of this attack. The 1841 expedition was abandoned as a result of illness amongst the party, of which over 50 died, mostly from Malaria. A number of African’s were in the party, none of whom suffered any illness, one of these was one Reverend (later Bishop) Samuel Ajayi Crowther.

The result of these two failures being that the British Government ceased offering subventions for any such expeditions, for the reason that they did not deliver the requisite returns on the Crown’s investment- this was business, simple. The policy mind- set in the Whitehall at that time, became firmly of the effect that there were no Imperial ambitions towards Nigeria, it was- in the view of British civil servants- not worth the trouble and expense. In the absence of Government sponsored expeditions, British presence in the lands surrounding the Niger, consisted initially of small, but determined and hardy traders, who entered into commercial agreements with local communities, often facing hostility, but generally doing profitable business, based on payment of taxes to local Kings (known as “comey” in the Niger Delta).

Notable figures included James Alexander Croft, often described as “the father of the River Niger”, James Pinnock from Liverpool and William Cole, (who established strong trading links around Aboh, Onitsha, Illah, Obosi and chronicled his travels in his book "Journal of an African trader") Miller Brothers of Glasgow etc. The key being that British Government vessels were too large and unwieldy to negotiate the tributary Rivers to the Niger, so as to penetrate the hinterland. The small traders on the other hand, traveled by Canoe with local guides and interpreters, building (and often destroying) relationships with local communities. These small individual traders were however largely insignificant by virtue of that same disorganised individuality and competition was rife and cutthroat with other European traders, especially French and German traders. In the absence of an organised political and administrative structure favourable to their objectives, they seemed almost destined to remain lone prospectors on the Niger’s territorial plains.

The “first amalgamation”

This prevailing state of affairs amongst the British traders was very soon to change. In 1877, a former British Army Engineer Goldie Taubman (later to become George Taubman Goldie) and his brother Captain Goldie Taubman, embarked upon a voyage up the River Niger, seeking to travel through Africa. Though unsuccessful, George Taubman Goldie, on this journey, developed his single-minded intention of Imperial acquisition of the Niger territories. He set about this task by working to amalgamate the disparate British trading interests under a conglomerate umbrella- no easy task at all, but of which he succeeded in 1879, by the formation of the United African Company. This being the united face of British Commercial presence in the Niger Territories. This single entity was a corporate Bull-dog of raw expansionist impetus, simply out-muscling rival European interests in the area. It consolidated itself with aggressive expansion – via treaties with indigenous communities and the acquisition of some of its rivals, with Goldie as the directing mind and engine room of this company’s phenomenal growth. It filled the niche which British Commercial trading interests had lacked-which simply was an organised legal and political entity, with size advantage.

Treaties were entered into with indigenous communities and the UAC built up armed capability, which it deployed quite forcefully in Brass, to dispel the Cannons of the Brass-men, who were adamant in defending the hinterland from incursion by the Europeans. It’s strategy in competing with rival European trading entities was quite simply to acquire those it could, and as described in the History of the Royal Niger Company (published by the RNC in 1887)- “to induce its foreign competitors to retire from the Niger and the Benue…”. It largely succeeded- though not completely- in achieving this aim. The operational face of the United African Company’s aggressive entry into the commercial land-scape of the Niger Territories was its pugnacious Agent-General- David McIntosh, a hardened veteran of the Niger and who answered to the gratuitously accorded nickname “King of the Niger” for his knowledge of and influence in the territories. The company’s staff complement consisted of British veterans of the Niger, educated African’s -mostly recruited from Sierra Leone- as clerks and middle-level Managers and indigenous people of all ethnicities, as labourers and armed Guards.

This company, evolved in 1882 into a new company- the National African Company, which was a result of the purchase of the interests of the British Companies constituting the United African Company. The main objects of the company being:

i. Political and commercial development- “the former only as a means to the end of the latter”;

ii. That such development should be in the hands of a single company, so long as no legal Government shall exist;

iii. To obtain by special clause in the Memorandum of Association, International status by the grant of a Royal Charter from her Majesty or in the absence of that from another power. This became necessary – as a requirement of International Law at the time, that the acts of such a company would not be valid against a Sovereign State entity, unless it possessed a Charter from another Sovereign State, to do acts as its representative;

iv. To bring into direct relations with the company, the Empires of Gandu and Sokoto

The RNC in the same year applied by Petition for a Royal Charter to represent and promote British Commercial interests in the territory. The essence of Charter being to give it formal seal and authority to act in the interests or as appointed agents of the British Crown. The basis of its Petition for Royal Charter was primarily as said to represent the Crown’s interest based on:

a. Its stated experience and expertise in navigating the hitherto inaccessible territories, located in the Niger hinterland, reachable via access through Inland water-ways, especially in the Benue and Niger Delta areas. The British Government had attempted unsuccessfully since the successful navigation of the Niger’s course in 1830, to penetrate the hinterland to extend its sphere of influence, The British Traders on the other hand had achieved this, with a combination of determination and adaptability. The British Traders in question, as said came under the conglomerate umbrella of the United African Company (or National African Company), thus brought this value proposition to the table.

b. The several Treaties (whether rightly or wrongly procured), it had entered into with indigenous territories, which represented tangible evidence of a working relationship with the indigenous communities. One which the Crown had failed to achieve before this, in spite of half of a century of trying;

c. The National African Company’s representation of its capacity to run the Niger Territories as a self-sufficient, going-concern, which would require no investment or financial intervention from the Crown.

All these, presented a not unattractive prospect to the British Government and in spite of some reservations expressed by groups of traders, such as the Liverpool Traders, the Charter was granted to the National African Company, which subsequently changed its name to the Royal Niger Company, to reflect its elevated status. Goldie had initially approached the Government- specifically the Conservative Peer Robert Cecil- the Marquis of Salisbury, to sound out opinion on the prospects of the Petition and was advised that whilst it was an interesting Petition, the Company’s low Share Capital base (£100,000) made successful consideration an impossibility. Goldie was to return with an increased, paid-up Share capital of £1 Million, consisting of 100,000 Shares of £10 each, of which 96,700 were fully paid up. An influential Chairman in the person of Lord Aberdare- then President of the Royal Geographical Society. In a very short time, the Petition was quite understandably viewed favourably and the Charter granted accordingly. It is also important to mention that the Marquis of Salisbury had in the intervening period, June 1885- January 1886, assumed office and served as Prime Minister.

Gazette copy of grant of Petition by the National African Company for a Royal Charter

The Government of the Royal Niger Company

The Royal Niger Company, quickly established formal structures on ground, consisting of two broad operational divisions, namely the Niger Government and the Commercial arm. The Niger Government was largely comprised of:

a. An Executive or Administrative office, located at the company’s Headquarters at Asaba and at which its Agent-General sat, in direct control of the local operations. The company’s station in the town of Akassa in the Atlantic Coast, of the Niger Delta, was its most important and busy operational hub. This office exercised functions that included infrastructural /Human resources management, Revenue collection etc

b. A Judicial authority, with Civil and Criminal jurisdiction, which was presided over by an officer described as a Commissioner, to adjudicate over disputes between communities who had submitted themselves to the RNC’s jurisdiction, by virtue of the individual treaties, as well as to handle charges and complaints against officers of the company. The authority also heard appeals from quasi-judicial decisions by the company’s District Agent’s in the first instance. Under its criminal jurisdiction, it could impose sanctions on African parties, however sanctions arising from complaints against Europeans, were required to be referred to the company’s Council (formerly Board of Directors before the Charter).

c. A Constabulary Force, Which was in essence a Para-Military Force, since its duties extended beyond mere Policing, but also to Military campaigns, pursuant to enforcement of the terms of Treaties and protection of the company’s assets. The Force, at inception, consisted of 153 officers and men, headed by a Commandant and assisted by a Sub-Commandant and a Gunnery Instructor.

The company operated according to regulations drawn up at its global Headquarters in London, as complied and ratified by its Council, chaired by Lord Aberdare and with George Goldie, its Vice-Chairman, as de facto Chief Executive Officer. Its Commercial operations whilst distinct in formal terms, were managed by the same individuals who ran the Government.

The company’s strategy was devised quite astutely and implemented with ruthless effect by Goldie. This being to build a trade monopoly for itself, within the land territories of the Niger for which it had control. This being achieved by monopolising the supply of imported goods to local communities, whilst at the same time manipulating the price at which the said communities supplied goods (Palm produce, Ivory, She Butter etc) on barter to It, in exchange for the said Imported goods. The resultant effect being that local suppliers were forced in to supply at prices well below that in the neighbouring Oil Rivers Protectorate and other territories.

Whilst the Berlin Conference expressly prevented a monopoly of trade on the River Niger, Goldie responded to complaints of its clear monopoly by stating that its tariffs as complained of (the method by which it had driven away competition) were only applicable and perfectly permissible on vessels, berthing and trading on its territory and did not affect navigation on the Niger, which the agreement arrived at the Berlin Conference had sought to protect. These issues aside, the RNC was extremely effective in carrying out its brief, with a combination of negotiation (some would say with deception) and often with the use of

force.

It had just before the Berlin Conference, entered into several treaties with indigenous communities, putting them under its control. Most significantly it had either driven away or bought over its biggest commercial competitors on the Niger - the French Trading Houses, especially the powerful Compagnie de l’Afrique Equatoriale. This intimidating control of the Niger Territory had given the British Government, the advantage of a fait accompli to present to the conference.

The company’s advancement of its controlling influence was rapid and aggressive, under the eagle-eye, commercial acumen and iron fist of George Goldie. On the ground in the territories, the single- minded determination and abrasive style of its Agent-General, David McIntosh, was evident in the nature of the spread of this influence. Its commercial successes were well recorded, with the acquisition of several Steamers and the establishment of over 50 busy trading stations, in various locations in the Niger Territories. The glaring smears on this cloak of power and influence, manifested fundamentally in procedural and substantive irregularities in many of the Treaties it procured, which even the British Colonial authorities had to acknowledge. In addition, its accounts over the years were in continuous deficit, specifically its accounts for the first 6 years after the grant of Charter showed a cumulative deficit of £162, 374. 00, or an average annual deficit of £18,024.00. This served to fuel further criticisms of the company by those who had consistently opposed the grant of its Charter. These criticisms were in any event to be expected, on account of the competitive nature of the RNC’s tenure, i.e to hold of Trade monopoly- under the instrument of political control by proxy, for a major world power -the British Crown, against the opposition of erstwhile competitors or new entities with competing commercial interests.

The grant of Charter to the RNC was, even beyond the peculiar question of the RNC’s conduct or personality, already a fraught ideological issue, with the polar opposite contentions held by those who opposed Governance by a Trading Institution and on the other hand, those who felt that the Government should not involve itself with the promotion of trade, preferring that commercial institutions instead be empowered- as the RNC was, to pursue this task. Nonetheless, the RNC endeared itself to few, aside from those with whom it held favour in Whitehall, who would stand in its defence in response to what were myriad complaints and Petition’s against its conduct. One of the most comprehensively detailed complaints about the RNC, being as referred to above, being from Harry Johnston, Vice-Consul in the Oil Rivers Protectorate. His three page representation to the Colonial Secretary in 1888, was quite excoriatory of the RNC, evidenced by the following quote: “It has to be confessed that in the two years, since the grant of a Charter to the company, its conduct has been a source of disappointment to its friends and exasperation to its enemies….whole districts which used to be friendly towards Europeans, are now impassable from their dogged hostility…”

George Goldie and the RNC even managed to rouse the ire of the much loved and mild-mannered Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther, who had been instrumental to the spread of Christianity in the Niger hinterland (he had also been involved in the ill-fated Niger expedition of 1841). Goldie was unhappy with the evangelical work of the CMS Church in the Niger territories, not because of he had any fundamental issues with the Church, but more on account of the said evangelism being spear-headed by African Priests, as was Crowther’s policy. Additionally Crowther was scathingly critical of the RNC’s conduct in the Niger. It is interesting to mention- as an aside, that the CMS Church leadership in London, did not share Crowther’s view and were in fact, staunch supporters of Goldie, based on his anti- liquor policy in the territory, so much so they were prepared to ignore serious acts of oppressive conduct by the RNC. It is equally necessary to mention that the CMS Church leadership at that time, also shared Goldie’s disdain for African Clergymen.

There was also a celebrated complaint by the German Firm Hoenigsberg, which complained generally about oppressive and unfair trading practice by the RNC-and specifically the blocking of the firm’s vessels access to the River Niger- even after payment of the requisite licence fees- a fundamental term of agreement of the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885. The Conference had ceded control of the River Niger to Britain, on the condition of free access to vessels of other nations.

Whilst the company had the favour of the Marquis of Salisbury, it weathered the storm of each wave of criticism, which seemed to embolden its Agents further in what progressively became a corporate culture of oppressive conduct. To understand the basis of Salisbury’s support, one must study his ideological positions and Parliamentary record. Salisbury was an ultra-Conservative, who had:

a. Opposed the extension of suffrage rights envisioned by the UK Reform Act of 1867;

b. Favoured aggressive Military expansionism. This was exemplified by a discussion in Cabinet, pursuant to a proposed attack on Mytilene in Greece, he is quoted in the Cabinet Papers as stating : “if our ancestors had cared for the rights of other people, the British empire would not have been made…”.

These examples being to illustrate the seeming affinity between Salisbury’s personality/philosophy and Goldie’s. The two men being united by a single-minded -and it must be said- fervently patriotic commitment to the furtherance of British political and commercial interests, with little sensitivity for liberal considerations.

The Royal Niger Company and the abortive “Second amalgamation”.

The Oil Rivers Protectorate, was established in 1884, as an outcome of the Berlin Conference of the same year and consisted of seven distinct states- Bonny, Forcados, Old Calabar, New Calabar, Benin, Brass and Opobo. This Protectorate remained under the control of the British Crown, whilst the Royal Niger Company retained control of the territories which it had procured treaties with indigenous communities. The effect of this being that there were two governing authorities for what was in the most part, two neighbouring territories.

In 1887, discussions commenced in the Colonial Government- not unlikely as a result of impetus from Goldie- regarding amalgamation of the Oil Rivers Protectorate with the Royal Niger Company’s territories. This aroused almost instant objection from the RNC’s now conventional opponents-

a. The Lagos traders/Government of the Colony of Lagos. Lagos traders (both European and Indigenous), had beyond doubt been disadvantaged by its restrictive policies on the Niger, namely- imposition of exorbitant tariffs and licences, which had forced almost all of them to abandon their trade in the Niger Territories, the same of which had thrived before the grant of the RNC’s Charter. Governor Alfred Moloney proactively forwarded the traders “Memorial” (summary of their grievance) to Lord Salisbury, the same of which had categorically challenged the proposed extension of the RNC charter to the Oil Rivers. Moloney had additionally sent his own memorandum to Lord Salisbury, detailing his objections to the amalgamation of the Oil Rivers with the RNC Territories and an actual proposal that the western territory of the Oil Rivers (from the Forcados River, or Itsekiri land) be annexed to the Colony of Lagos and the rest retained as Government Protectorate;

b. European traders in the Niger territories, who equally had been subject to the RNC’s restrictive trade practices. This category consisting primarily- and quite ironically- of British Traders, especially the influential Liverpool Traders, who were vehemently opposed to the company’s monopoly. There was also the small but vocal German opposition represented by the sole German trader on the Niger- Hoenigsberg, who as said, had engendered a diplomatic row between its own Government and the British Crown, further to the incident of its vessels being blocked and seized by the RNC.

c. The British Consulate in the Oil Rivers, headed by Consul Hewett had a year earlier, complained to the Colonial Office in London about the suspect nature of the 37 Treaties, which the RNC had based its influence In the Niger territories. His categorical comments in relation to the nature of rights accorded the RNC by the treaties being that “no such rights would be recognised by Her Majesty’s Government, under the Protectorate”. In specific reference to the intended amalgamation, Vice-Consul Harry Johnston, expressed rather starkly in memorandum to Lord Salisbury in 1888, that the RNC’s oppressive conduct had destroyed erstwhile cordial relations with indigenous communities in the Niger territories and further that in principle, it was wrong to entrust further territorial control in the hands of a trading institution. It is interesting however, to note that Johnston was the Colonial Official responsible for what may be described as the abduction of Jaja of Opobo, an act decried even in Britain.

d. European Governments- especially the German Government, whose view was that the RNC had contravened the terms of the treaty signed at the Berlin Conference, which though acknowledging British control of the River Niger (from the Niger Delta, up to the area just beyond Borgu), agreed that there would be free navigation of the River, subject to payment of any costs of passage, strictly restricted to the basic expense of administration. The RNC had obviously breached this, by charging extremely high duties and licence fees, sometimes amounting to 40% of the value of cargo.

There ensued the usual round of contentious correspondence from all sides of the argument, with the Traders and other parties raising written objections to the extension of the Charter, and with the company through the pen of Lugard and his lieutenants, marshalling robust defence of the company’s stewardship, especially highlighting its feat in opening up the hinterland territories of the Niger thus guaranteeing British control of the River Niger. The RNC especially highlighting the embarrassing failure of the Government sponsored efforts in this regard in earlier years and by extension the folly in Governments supervising commercial enterprise.

In parallel with this, the powerful trader groups (curiously) entered into intense negotiations with the RNC further to a new broad amalgamation of all trading interests on the River Niger. Whilst this would have been a historic consolidation of British commercial power on the Niger, its very possibility sent ripples of fear down opponents of the RNC and what the proposed amalgamation would stand for ultimately- a Leviathan trader Government. The resultant outcome of all the horse-trading came to a head, not based on the efforts of the RNC’s conventional opponents, but from the powerful lobby of the big British Shipping companies (Elder-Dempster, The African Steamship Company etc), their efforts, with the minor impetus of the conventional opposition formed a critical mass, that the RNC’s normally formidable political lobby machine, could not forestall. The intended amalgamation of the Oil Rivers Protectorate and the Niger Territories was placed permanently in abeyance. This was the first major political battle the RNC or in effect, Goldie had ever lost and as events unfolded in ensuing years, it was not to be the last. The slide to defeat in the political and commercial civil war for the Niger Territories, had just begun for the RNC.

The decline of Influence:

The aftermath of the lost battle for amalgamation with the Oil Rivers territories, was to witness a cold, merciless, realignment of forces against the RNC and a further conspiracy of fate against it, which in the eyes of impartial observers was a deserved consequence of its own conduct and the imperfections of its own operational model- which had ironically been its greatest strength.

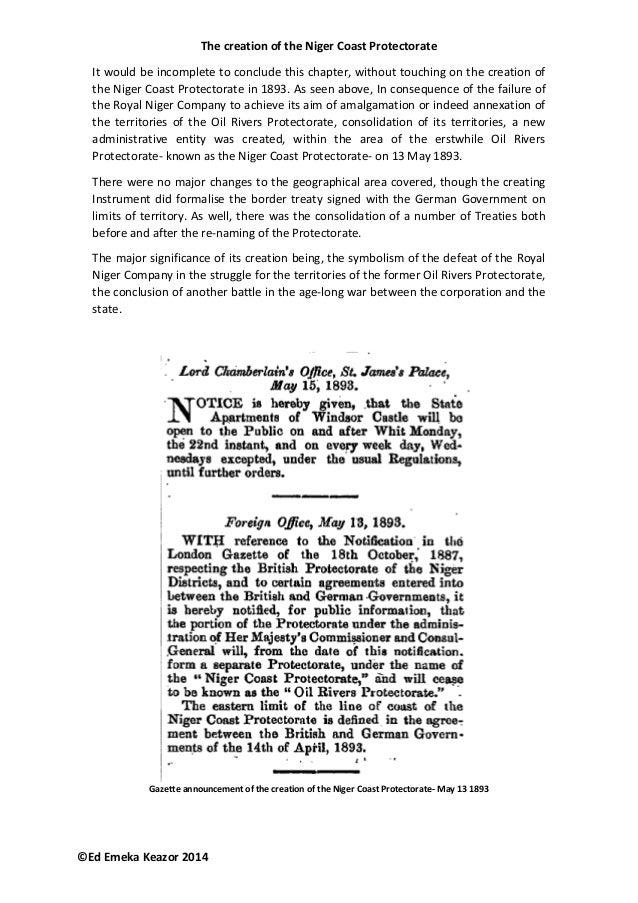

The first challenge faced by the RNC was the appointment of Sir Ralph Moor as Consul to the Oil Rivers Protectorate in 1891. Moor was vehemently against its monopolist practices and other excesses in the territory and thus became a committed and influential foe, the Oil Rivers Protectorate was additionally to be renamed the Niger Coast Protectorate in 1893. In addition, the traders who had recently been potential partners of the RNC, reverted to their role as bitter rivals and competitors, revising their strategy to break its monopoly by drastically raising the purchase rates they paid for Palm Produce- whilst operating in the neighbouring Oil Rivers Protectorate- so as to encourage smuggling of the same into the Oil Rivers Protectorate. They deliberately traded at a loss, with a view to comprehensively weakening the RNC’s monopoly. This was to fail, on account of the underestimation of the sheer will and guile of Goldie- in 1893, he bought out the interests of these traders who had operated under the collective name and style of the African Association, a resulting entente was agreed, with each company restricting itself to its own territory- in a dual monopoly.

The year 1895, was however to prove the crucial turning point in the RNC’s decline and fall. These being in the occurrence of two significant but unrelated events.

a. The appointment of Joseph Chamberlain as Colonial Secretary. Chamberlain was a Liberal Politician, with strong libertarian views and an avowed and robust opponent of Salisbury. He was appointed to the UK Cabinet, quite ironically in the course of the coalition with the Conservative Government- with Salisbury as Prime Minister. He deliberately chose appointment to the post of Colonial Secretary, demurring the opportunity of higher appointments, with the singular objective of influencing Government policy in the Colonies and Protectorate territories. His objective being the development of the West African territories as part of his own distinct Imperial philosophy. He had a strong pro-active approach to the protection of British interests, especially in West Africa. Like Salisbury though, he was extremely suspicious of French adventurism in the sub-region. France had by now established direct acquisition of Territory, abandoning the previous method of individual consensual treaties with individual communities. Chamberlain pushed for a more robust Imperial presence in the Niger Territories, especially as the French had made incursion into the RNC’s territory such as establishing a Fort at Bussa, with no response from Goldie- on account of the RNC’s Force being tied up at Akassa, defending an attack, which is discussed in detail below. The West African Frontier Force was established in 1897, in furtherance of this aim, under the command of Colonel Frederick Lugard and placed under direct British Government control. This being inspite of Lokoja, its headquarters, being within RNC territory, clear symbolism that administrative control was slipping from the company’s hands- a fact that was not at all lost on George Goldie. The WAFF had as said been deployed to forestall further French incursion and a near state of war nearly ensued as both Armies faced off to each other in 1897. This was averted by the French relinquishing their claim to Bussa and the Treaty of Borgu was signed, giving the French free access from Borgu in the north, all the way down to the Coast. This was one of the most significant decisions taken, since the Conference of Berlin, which was to impact on the Niger administration in a manner to be seen later.

b. The raid of Akassa by the Brass people

On 29 January 1895, a 1000 strong force of the Brass people, in over 40 canoes, led by their King Frederick William Koko Mingi VIII, attacked the RNC’s station at Akassa, destroying property and taking over 60 white staff hostage, removing goods, money, arms and ammunition, from the warehouses and burning the buildings thereafter. The basis of this action was simply pent-up frustration from years of oppression by the RNC against the people of Nembe.

Prior to the RNC charter, they had admittedly been strategic middlemen between the European traders and the hinterland trade, however with the advent of the RNC and its restrictive monopoly, they had literally been driven to starvation and the wisdom behind their actions being that they would rather die fighting, than die of hunger- the natural consequence of continued quiet acquiescence to the RNC’s oppressive conduct. Koko Mingi who had in fact been an educated Christian School-teacher (before renouncing Christianity on account of resentment with the RNC), had written to the British Consul at the Niger Coast Protectorate- Claude Macdonald, explaining the position of the Nembe people, stating that their problem was with the Royal Niger Company and not the Queen and the British Government. He requested as a condition for the release of the hostage’s, the return to the pre- existing trade practices before the advent of the RNC. Macdonald was sympathetic to the Brass people and acknowledged that these were complaints he had heard for over three and a half years, but had little power to remedy. Koko Mingi’s demands were not accepted and, 40 of the hostages were killed and eaten, in a symbolic act of revenge against the RNC. This symbolism being in the tradition of the people then, as a demonstration of superiority and complete defeat of an avowed enemy.

The British were compelled to mount a reprisal attack on 20 February 1895, a Naval force led by Admiral Bedford, attacked Nembe, razing it to the ground at the cost of 300 lives and many more through a concurrent Small-Pox epidemic. Macdonald in spite of this still maintained communication with Koko Mingi (who at this time had gone underground), and the latter responded in turn, seeking to convey his limited involvement in the killings (an account which was later discounted by other Nembe Chiefs), by effecting an exchange of prisoners and the return of a Cannon and Machine-Gun, removed from the RNC’s Akassa warehouse. The overall effect of this was that regardless of the killing and eating of the 40 RNC staff, the British press and public harboured deep sympathy for the Brass people, fully empathising that their actions were as a result of deep provocation from the RNC. The resultant effect was that a Commission of Enquiry was set up under the Chairmanship of Sir John Kirk, an Anti- Racism campaigner, to comprehensively investigate the complaints of the Brass people. Koko Mingi never surrendered to the British and fled to Etiema, where he died in 1898.

The Kirk Commission of Enquiry

The Special Commission- Niger Territories, had as its remit, the investigation of the cause of the disturbances represented by the Akassa raid and an investigation of the complaints raised by the Brass people against the Royal Niger Company. It was headed by anti-Racism campaigner- Sir John Kirk, who was deemed of solid credentials, to ensure a robust and credible investigation of the grievances of the Brass people, as well as to arrive at a fair consideration of all the relevant issues.

The Commission began its public hearing on 10 June 1895 and heard evidence from the Brass people, comprising four Principal Chiefs and sixty other indigenous witnesses, with Kirk insisting on meeting the Brass people in camera absent of the RNC representatives, so as to obtain an unrestrained account of their grievances before the main testimony. The Brass people were represented as Counsel by Captain Harry Gallwey, Vice-Consul of Benin (later to play a part in the Invasion of Benin) W.Wallace, the RNC’s Agent-General gave testimony on its behalf.

The evidence of the Brass people was in two parts, the Chiefs gave evidence generally about their relationship with the RNC and specifically to clarify details contained in their Petition. Sixty witnesses gave evidence of acts of maltreatment and oppressive conduct, ranging from attempted Murder, to Rape and Assault. The RNC called several witnesses in rebuttal, the summary of its defence to the charges being that the smuggling of arms into its territory, as well as produce out of it was rife, hence it was compelled to resort to strict measures to curtail this, whilst seeming to deny other allegations of maltreatment levelled against it.

Claude Macdonald, continued to champion the cause of the Brass people, decrying the oppressive conduct of the RNC in his statement to the enquiry, an excerpt of which was as follows: “They can open and shut any market at will, which means subsistence or starvation to the Native inhabitants of the place. They can offer any price they like to the Producers and the latter must take it or starve. The reason why, is that the company’s dividends. Why should not the producer sell his stuff to the best advantage, and to whom he likes? He is the aboriginal and the tree whereupon the palm-nut grows is his. No he must sell it to the company or starve. In their territories are thousands of villages engaged in the palm oil trade or would like to be, for the oil is growing at their doors, but the ports of entry at which they are allowed to trade are comparatively few in number, so that there are tracts of oil producing country, not worked at all. Why could not duty be paid at the door and trade where you like, as at Accra, Lagos and the Protectorate?” Kirk’s report was to the effect that the Royal Niger Company had imposed a Monopolistic regime that had the effect of unfairness against the Brass people, excerpt of his comments being thus: “The rules in force are practically prohibitory to Native trade and the Brass men are right in saying this is so. They are for all intents and purposes excluded from the Niger, if they are to respect these regulations”.

The regulations in question being, for the avoidance of doubt, the requirement of licence fee of £150 per canoe to ply in the RNC’s territories, in addition to duty payable on goods. The same of which had proven a hindrance to better positioned European traders, much less the impoverished people of Brass. This licence fee being payable by RNC regulations, as Nembe was within the Niger Coast Protectorate and outside of the RNC’s territory.

Kirk’s report did not attribute the burden of fault on any particular party- in short a neutral verdict, however, damages were awarded in the sum of £20,384.5s 6D, to the RNC, in compensation for the material losses it suffered. Additionally, the people of Brass were fined £500, which was later paid by sympathetic European traders. The panel however was, as said, highly critical of the RNC’s conduct and condemned the naked Monopoly it exercised over the Niger Territories, recommending the dismantling of this forthwith. It proposed a modified structure of Governance for the territories, known as “the Kirk plan”. The summary being: Transformation of the RNC into a purely administrative body, with a £400,000 Share capital, paying an annual dividend of 5 per cent sourced from a modest margin of profit after deduction of expenses.

Records of proceedings of Special Commission of Enquiry- Niger Territories, convened to investigate the complaints of the Brass people in 1895.

Records of proceedings of Special Commission of Enquiry- Niger Territories, convened to investigate the complaints of the Brass people in 1895.

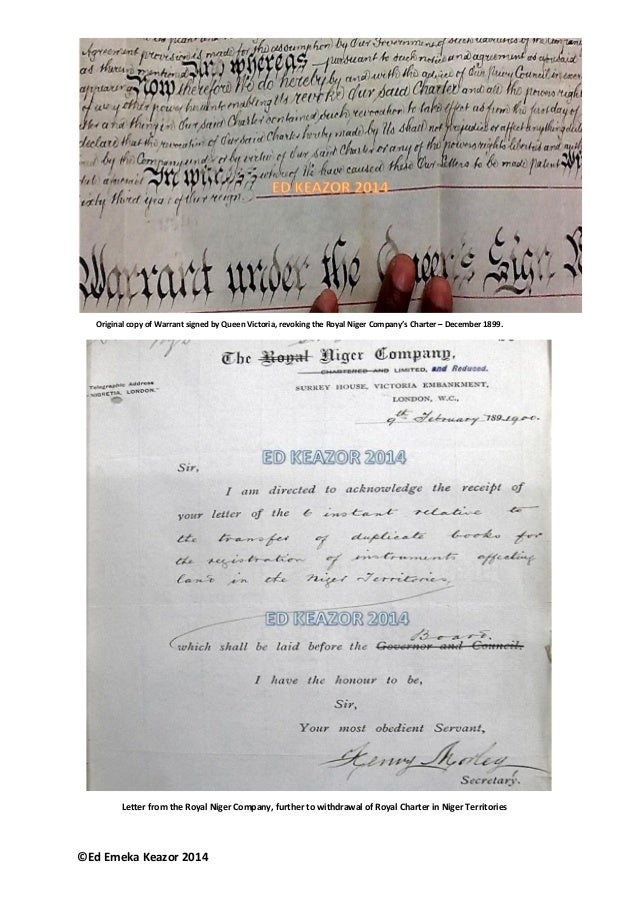

The withdrawal of the Charter:

The Kirk report did nothing to improve the RNC’s popularity in Britain, naturally reinforcing the conception in the public mind of an unjust and oppressive tool, which offended the British public’s sense of fairness. Institutional opposition continued to mount against it both in West Africa and especially in Britain, as well in France and Germany.

The combined effect of the public relations disaster that was Akassa and the presence of a politically formidable opponent in Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, signalled the end for the Royal Niger Company and as far back as 1896, the process of revocation of its charter commenced. The RNC was in spite of its difficulties, still capable of exerting its influence, as demonstrated by its conquest of the Emirates of Nupe and Ilorin in 1897, in which it defeated both Armies. It was however to face humiliation a year later, when the Ekumeku resistance sacked its Headquarters at Asaba in a surprise attack in 1898, the tide was only turned with the deployment of reinforcements from Lokoja, where some troops were stationed. The end of an era was formally signalled when Sir Ralph Moor, High Commissioner to the Niger Coast Protectorate, made proposals for the revocation of the RNC’s Charter, pursuant to which a report into the consequences of the revocation was commissioned and written by Civil servants- Sir Clement Hill and Mr Ryder, of the British Foreign Office.

The report examined in detail, the provisions of the RNC’s charter and indeed the methods, through which the relationship was best severed and what the consequences would be. The end result was simply that whilst the charter provided no legal consequences for revocation, there would be a public uproar at the injustice of it, since it was widely acknowledged the RNC had incurred huge costs and had an obligation to its investors, which would have taken several years to recoup. Their report arrived at a compensatory sum of £500,000.00. The same gentlemen equally reviewed the same, a year later and upwardly revised the proposed payment to £700,000.00 Goldie in the interim, as astute as ever, had seen the writing on the wall and as engaged in intense behind-the-scenes negotiations with the Chancellor of the Exchequer, on possible compensation for its investments in the Niger territories. The settlement was finally agreed in the sum of £865,895 of which £556, 895 was paid directly to the Company. Also the government agreed to pay the Company one-half of all royalties on minerals produced in what would become its former Territory for a period of 99 years.

The revocation of the Royal Niger Company’s Charter was first officially recorded in a letter from the Foreign Office to the Treasury, written in June 1899, after the terms had been agreed, notifying of the proposed revocation. The bases of the revocation, as expressed in the letter being as follows:

a. The effect of the Treaty of Borgu, referred to above, which gave the French free trading rights access on the River Niger, down to Bussa, with the British retaining sole access from Bussa down to the coast, thus subverting RNC control over the Niger;

b. The various complaints of Traders about the RNC’s monopoly and conduct;

c. The need for Imperial control over the new Royal West African Frontier Force.

Memorandum by Messrs Hill and Ryder, regarding possible compensation for the RNC on revocation of Charter.

Memorandum by Messrs Hill and Ryder, regarding possible compensation for the RNC on revocation of Charter.

West African History, which would be recalled by most with less than fond memories. However what could not be ignored was the sheer determination and pioneering effort that was evident in the company’s achievement in opening up the Niger hinterlands to trade, however the fact of at least two strategic actors, referring to its entry into those lands “as a curse”, will always taint its legacy on the Niger. The company became just the “Niger Company” from January 1 1900, which was indeed reflected in its Registry records and letterhead’s. The Niger Company, inspite of losing its charter continued to thrive as a corporate body, still enjoying the vestiges of its near monopoly on the Niger. It increased its share capital to £3 Million in 1914 and was eventually bought for £8.5 Million in 1920, by Lever Brothers. In 1929, it was bought by the Unilever Group and thereafter traded under its original name- the United Africa Company, under which it remains today, now as a part of the Unilever Group.

It is important to mention that in 1937, there was a review of payments made to the RNC by virtue of this settlement, as part of review of obsolete acts of Parliament, which the Royal Niger Company Act of 1899 had become, by the liquidation of the Charter Company. It is noteworthy that a fundamental finding of Sir Ormsby-Gore, who conducted the review and which he made known to the House of Commons on 28 June 1937, was as follows:

“As soon as settled government was established the company gave way to the Imperial Government. The area in which the company operated comprised a series of native areas with whose chiefs the company had made treaties, but the "treaty" area did not coincide with the area administered. In fact the company's administrative activities and expenditure were limited to the vicinity of the rivers, that is the River Niger and its tributaries on which they had established trading stations. This is borne out by the fact that their expenses of administration of the native territories at the date of transfer did not exceed £50,000 a year. “At no time in the past, however, has there been any precise definition of the territories administered by the company, and after the passing of the Act no such definition was practicable, nor it is practicable at the present time. Fifteen years later, all the territories in this part of the world formed part of the Dependency of Nigeria, and consequently if any sums were due they would be due from the whole of Nigeria. It would be impossible to assess them because the company has long since ceased to exist, and this Resolution is necessary in order to lead up to a one-Clause Bill wiping out to the satisfaction of the Public Accounts Committee and everybody concerned Section 3 of the entirely obsolete Act of 1899.”

Noel Goldie, member of Parliament for Warrington raised a question as to how far the Statute of Limitations would apply to a company of the nature of the RNC, to which Ormsby Gore’s response was terse and instructive: “The company ceased to exist 38 years ago. The Public Accounts Committee discovered in 1935 that this Section was still on the Statute Book, and it is only right that an obsolete provision of this kind, when found, should be removed.” The House adjourned resolution till the next date and came to the following conclusion, which was the final line drawn on the RNC’s dynasty in Nigeria:

"Resolution reported, That it is expedient to remit any sums which have become or may become payable to the Exchequer under section three of the Royal Niger Company Act, 1899, and to extinguish the liability for the payment of such sums." (Hansard HC Deb 29 June 1937 vol 325 cc1925-6).

Memorandum of W.Ormsby-Gore- Colonial Secretary on propriety of compensation payments to the RNC – Jan. 1937.

Memorandum of W.Ormsby-Gore- Colonial Secretary on propriety of compensation payments to the RNC – Jan. 1937.P.2

Conclusion

The Royal Niger Company via its alter-ego George Taubman-Goldie, was beyond any shadow of a doubt one of the most influential forces in the consolidation of British Colonial Interests in the Niger Territories and by extension, in the creation of the Nigerian State. There will always be legitimate questions about its ethos and operational methods. There have been clearly established doubts about the fundamental basis of its claim to influence in the Niger Territories, for the fact that a large number of the Treaties it based its influenced on (i.e with the Kingdoms and communities of the Niger Territories) were seen to have been procured either fraudulently, by coercion or indeed not at all.

The Royal Niger Company however served the ends of the British Crown, which was its principal in any event and whose service, in its own eyes, was its sole objective. The British Government in itself, based on the ideological disposition of the Conservative Government, which held the reins of power at the operative time, gave tacit approval to the RNC’s methods, because quite simply- they delivered on their assignment. Indeed the specific ideological disposition of the Marquis of Salisbury, the RNC’s main supporter within that Government ensured that even where there were any murmurs of dissent within Government, these were overcome quite comprehensively. This gave the RNC a feeling of invincibility which it reflected in an exponential exercise of what some might term megalomanic power in the Niger Territories, resulting in a corresponding increase in its opponents, both African and indeed European.

The turning point was beyond doubt the revolt of the Nembe people and the raid of the RNC’s station at Akassa. Whilst this would have been assumed to attract outrage in Britain, on the contrary public opinion there had acquired a liberal influence, which in spite of the Crown’s Imperial dominance, questioned the rationale of methods of exercise of the said Imperialism. The British public simply did not approve of the unbridled exercise of Imperial power in the Colonies.

This liberalism had an effective and strategically important poster-boy in the new Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, who was singularly focused on a more humanist and liberal exercise of Imperial Influence in the Colonies- the RNC’s philosophy and Charter were to put it mildly on a ticking clock. Additionally a fundamental but largely overlooked side-bar contest to the whole story being the age-old and lingering ideological contest between the role of the Corporation and the State in Governance. The State had tried and failed to establish British Influence in the Niger territories, whilst the RNC succeeded (ostensibly). However the wounded Lion of State Influence was not going to be subdued quietly as was seen.

The legacy of the RNC was, as said at the beginning of this summary, dual. Through the sheer energy, tenacity and endurance of its promoters, it had united operationally disparate, but common British commercial interests, creating one of the most powerful conglomerates south of the Sahara, which impetus could be said to have given rise to the eventual creation of the entity that came to be known as Nigeria. On the other hand, It could however be said to have promoted a culture of corporate deceit and oppressive conduct in Governance. Whilst it was hardly the first to promote this or indeed the worst practitioner of such, its perceived arrogance and sheer impunity won it few friends. The Judgement of posterity on its legacy will quite justifiably continue to hang in the balance of History.

Ed Emeka Keazor 2014

Labels: Edward Keazor, Frederick Lugard. Ed Keazor. Emeka Keazor, George Taubman Goldie, History of Nigeria, Nigeria, Nigeria Amalgamation, Royal Niger Company, United African Company

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home